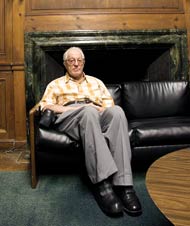

| The name Albert Ellis will

be very familiar to readers of Australasian Psychiatry;

Albert Ellis, MA PhD, founded rational emotive behaviour therapy

(REBT) in 1955, the first of the many cognitive behaviour

therapies (CBT). He was born in Pittsburgh and grew up in New

York City. Dr Ellis has published more than 800 scientific

papers, authored or edited over 75 books and monographs, and

produced more than 200 audio- and video-cassettes. As a

clinician, he has practised in psychotherapy, marriage and

family counselling, and sex therapy for 60 years. Currently, he

is president of the Albert Ellis Institute in New York City,

where I spoke with him on 17 June 2004. Dr Debbie Joffe,

currently a Fellow at the Institute, generously arranged our

interview. Dr Ellis dedicated his latest book to Dr Joffe. Our

far ranging conversation explored the impact of his childhood

illness, sibling relationships and parental divorce, teenage

struggles with dating, the effect of Bertrand Russell, Hitler,

Stalin and aftermath of the Second World War on his pacifist

philosophy, Hornian psychoanalysis, religion, God, mysticism,

his love of humour and singing as a 'shame-attacking' exercise

and, of course, inventing REBT.

G: I was told that you like to sing and that you have a

great sense of humour.

A: I have a lousy singing voice but I'm shameless, so I do

shame-attacking exercises.

G: And did you cultivate your sense of humour from your

family

is it your nature, or from living in New York?

is it your nature, or from living in New York?

A: It wasn't from family or anything like that because my

mother was not very humorous and my father was not around very

much. I didn't ever hear very much of his humour. He had some

sense of humour but I very rarely heard it. So I think I

cultivated it mainly by myself. I don't take anything too

seriously. I try to take much of life with a sense of humour.

G: Perhaps because you've delved to the very depth of the

human condition and use humour as a balance, to cope?

A: Partly, but I was first almost famous for my humorous

verse, which I published in several New York newspapers. Then I

started writing songs, serious and humorous. But at the American

Psychological Association meeting in 1975, we had a symposium on

humour and I sang some of these humorous songs. I was supposed

to accompany them with a tape recorder but the goddamn tape

recorder didn't work so I sang à cappela and I've been doing it

ever since.

G: Did your singing enhance your reputation or elicit

further criticism?

A: Both!

G: Perhaps later you could sing one of those classic

songs?

A: Right.

G: The title of your most recent book intrigues me,

Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy, It Works for Me

It Can Work for You (2004). In parts of the book, you

describe your near fatal illness last year. As the inventor of

rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT), you say REBT 'works

for me'. Does this reflect an element of 'physician heal

thyself' as integral to your life's work?

It Can Work for You (2004). In parts of the book, you

describe your near fatal illness last year. As the inventor of

rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT), you say REBT 'works

for me'. Does this reflect an element of 'physician heal

thyself' as integral to your life's work?

A: Yes, because I would probably never have invented REBT had

I not used something similar to it for myself when I was fairly

young. I was sometimes very anxious and I used humour on myself

and I used rationality which I got from reading philosophy.

I also was able to 'undisturb' myself out of my anxiety by doing

in vivo desensitization invented by J B Watson. So I used

it on myself and then later used it in psychotherapy.

G: In your book, you mention that you had quite serious

kidney problems for which you were hospitalized in early

childhood. Would you say you already used an early form of REBT

on yourself as a child?

A: That's right. My first hospital stay was at 5 ,

and at 6 ,

and at 6 I was in the hospital for 10 months. I did a great deal of

reading there and [also] when I returned home. I figured out

certain rational answers which weren't as good as my later ones.

I refused to disturb myself about my kidney problems and my

other physical ills.

I was in the hospital for 10 months. I did a great deal of

reading there and [also] when I returned home. I figured out

certain rational answers which weren't as good as my later ones.

I refused to disturb myself about my kidney problems and my

other physical ills.

G: So you used reading as a form of self-comforting.

A: The hospital had a library and I probably read every book

in it. I used to be able to take out two books a day from the

New York public library that I'd read and return the next day

and get two more. So from the age of about 6 or 7 I was a

voracious reader

everything, mainly fiction, plays, poetry and things like that,

but also enormous amount of science and non-fiction.

everything, mainly fiction, plays, poetry and things like that,

but also enormous amount of science and non-fiction.

G: Was your reading guided by a mentor?

A: No. I had a friend who taught me how to read before I even

went to school and I liked him and we got along. But he wasn't a

mentor and later I had others. One guy was about 3 years older

and I was very friendly with him and maybe he helped me

philosophically. But I don't remember if he did.

G: So would it be fair to say that already the 5 year-old

Albert was healing himself? year-old

Albert was healing himself?

A: I would say definitely so.

G: Now where do you think a 5 year-old little boy gets the

notion that rationality can soothe his worries?

A: Well, mainly from the fact that I was feeling disturbed. I

was anxious and somewhat depressed when my parents didn't show

up regularly at the hospital, so I didn't want to be miserable.

So I said to myself, what will I do not to be miserable and I

figured out some of the rational techniques which I used later.

My solutions were pretty good but not as good as the later REBT

solutions.

G: So the seeds of REBT were already growing from the age

of 5?

A: Right.

G: Do you remember if you used this method of coping as

you were growing up during adolescence, for yourself or others?

A: Mainly for my brother who was a year and a half younger

than I. If he got upset about anything I showed him how to do

what I had done. But I also talked to my friends about their

emotional problems.

G: Did your brother appreciate your input?

A: Oh yes, he was very rational, very sensible

a sane individual all of his life. Maybe he would have been

without my help, but I did seem to help him.

a sane individual all of his life. Maybe he would have been

without my help, but I did seem to help him.

G: You claim some credit perhaps?

A: Right.

G: And your sister?

A: She was 4 years younger, a screwball, a depressive from

day one. But much later on in life she read several of my books

and made herself less depressed.

G: A 'screwball', do you mean that in a technical sense?

A: No, sadly enough she was severely personality disordered.

She was very depressed and angry most of her life.

G: So how did you feel not being able to offer her

something to soothe her in a way that worked for you and your

brother?

A: Well, at first I disliked her. My brother hated her and

never got along with her, and I disliked her immensely. Then at

the age of 15, on the way home from a movie that was about angry

people, I decided that my anger wasn't doing me or her any good,

or anybody any good. So I figured out that I would forgive her

for her sins and let her copy my songs. Because I collected

songs at that time that she copied and messed up. My brother

didn't forgive her until years later, but I used my philosophy

of unconditional other acceptance with her from the age of 15. I

got myself to hate her behaviour, but not to hate her.

G: After adolescence, you've already tested, in a manner

of speaking, your technique on yourself and family. Any other

people?

A: My best friend Eddie probably was pretty disturbed

himself, so he kept asking me what to do about his family

problems. He had to cope with a rather disturbed brother also. I

helped him probably a good deal. That was mainly when I was a

teenager and older.

G: Now you mentioned that during your childhood your

parents didn't turn up as often as you would have liked to the

hospital. Later they separated and divorced.

A: My father only visited me maybe once when I was in the

hospital for 10 months. He was very busy, a businessman. My

mother visited me once a week, while other children were visited

twice a week, because she had two younger children and then at

times she went away to Wildwood, New Jersey for a 2 month

vacation. Usually she visited me once a week on Sunday.

G: A modern perspective would suggest that you were an

abandoned child?

A: Yes, and I have a chapter dealing with this in Rational

Emotive Behaviour Therapy It

Works for Me, It Can Work for You. It

Works for Me, It Can Work for You.

G: So as a young child you work out a way to cope with

your early abandonment. You then offer your method to your

brother, and later to your sister. Did you also use the method

to cope when your parents divorced?

A: Yes. They didn't tell us about it at first. I heard my

mother talking to my aunt once when I was 12 and found out that

they had got a divorce. My father had been away a great deal so

that wasn't so unusual, but they did get a divorce. My mother

took it reasonably well and I was never really upset about it.

G: Children can have strong reactions at such times.

Having become self-reliant to cope with earlier hardships, could

you have immunized yourself to deal with your parent's divorce?

A: Yes. When my parents were living together, my father would

be away for weeks at a time on business trips. I describe in the

book that we kissed him good morning about 8.00 a.m. while he

was still in bed, and then we saw him the next morning. Because

he was at work and doing all kinds of things during the week,

when he was home on Sunday he played pinocle or poker all day

with his friends. So he was not a very good father, and he

wasn't there for me or for his other two children. My mother was

also more interested in her friends than in her children and was

not nasty, but was neglectful.

G: Later in life, did you offer your techniques to your

mother or father?

A: Very rarely. I had conversations with my mother; I

probably told her not to take things too seriously. But she was

not a depressive, she was okay and very, very sociable. My

father really wasn't around very much to talk to.

G: Returning to your adolescence, you describe in your

book that around the age of 12, while preparing for your Bar

Mitzvah, you had a revelation of sorts about the absence of God

and the inadequacy of religion.

A: Right. I became a probabilistic aetheist, meaning that in

all probability there is no God, no Allah, no Zeus. They simply

don't exist, which is an idea I got mainly from reading the

literature, Bertrand Russell, H G Wells and others. If God does

exist, then he's not going to be a sadist and cut my balls off

for not believing in him. So I will assume that he doesn't exist

and go about my business.

So, a probabilistic aethiest is not a dogmatic aethiest who

says that there is no God and that there can't be. He says that

in all probability there is none and therefore, since the

probability of there being a God is 0.00001, I will assume there

isn't any deity. If there is, and if he ever comes and talks to

me, I'll ask him to prove that he really is God.

G: Has that happened yet?

A: No, he hasn't appeared to me and I've lived very well

without his help.

G: There's always revelation.

A: Right, if you are crazy enough to believe in it.

G: Now at one level that sounds provocative, maybe

jocular. But at another level, you say it with complete

seriousness. You've thought this through and actually arrived at

this position as rational and reasonable. Maybe the only

reasonable rational conclusion?

A: Right. I've had some help from a good many philosophers,

and in the vast amount of fiction and non-fiction that I've

read, up to and since the age of 12.

G: Having read so widely, did you subsequently meet any of

those authors?

A: No. Later when I was in college, I invited several of them

by writing them in verse. I invited Ogden Nash and other

writers. Some of them came to talk to the psychology club. So I

met them then, but when I was very young I don't remember

meeting any authors. I was always reading.

G: Moving from college, where you graduated in business

administration, in graduate school you turned to psychology.

Why? What made you choose psychology from all the possibilities?

A: Well, like I think I say in the book, I was a political

and economic revolutionist at the age of 19, but I got

disillusioned by Stalin and Hitler and I was against the

American communist party. I was an American revolutionary like

Thomas Jefferson. But then I saw that revolution was going

nowhere, so I decided to give up political revolution and

decided to go for sexual liberty, to promote a sexual

revolution. So I read hundreds of books and articles on sex,

love and marriage and became a scholarly sexologist.

G: In your chapter, 'My Philosophy of Sex Revolution',

you highlight the political intrigue that surrounded your

election as the first President of the Scientific Study of Sex.

You mention that one of your friends, Hans Lehfeldt, said that

you were too 'dangerous' for this position and he almost blocked

you from getting it. What made you so dangerous?

A: Well, at that time, that was about 1956, I had written two

books, The Folklore of Sex and The American Sexual

Tragedy, and I was a scholar but known to the public

already. Hans thought that The Society for the Scientific Study

of Sex, which I founded, was too respectable to have a

controversial sex revolutionary like me for its president. In

spite of some opposition, I still got elected as its first

President.

G: So one reason for being labelled 'dangerous' was simply

being ahead of your time?

A: Yes, I was already becoming too public. The people who

founded the Society with me were very liberal, sexually, but

they weren't publicly popular. Hans was afraid that my public

support would be disruptive, but it wasn't clear what the danger

was.

G: Prior to this period in the mid-1950s, you practised

psychoanalysis for 6 years. I read a quote of yours that

suggested that it was more or less a wasted 6 years.

A: Yes. I was trained in liberal psychoanalysis by a

psychiatrist who was a fellow of the Karen Horney School. I

practised psychoanalysis from 1947 to 1953 and then I abandoned

it.

G: After the Second World War, in 1947, you earned your

PhD in psychology. But prior to and during the war you were a

revolutionist. Did that arise partly from being disillusioned

about human nature?

A: Well, the Second World War helped make me a revolutionist

as there was so much badness in the world, including the war

itself. Then Hitler came in to make things much worse.

G: Clearly, war expresses the fact that some conflicts

only killing might resolve. How did you reconcile that with your

evolving thoughts in relation to what would later become REBT?

How did the confrontation with the reality of the war impact on

your thoughts?

A: Well, I was always a pacifist, even before I was a

therapist, because I was influenced by Bertrand Russell and

people like him. So when I formulated REBT in 1955, I decided as

one of its main essences, to help people accept themselves with

their flaws, and to also accept other people unconditionally.

REBT says that people's thoughts, feelings and actions are

often immoral but that they are not bad people.

G: You say in effect that you didn't damn Hitler, although

you did damn his actions and worked vigorously against them.

A: Yes. To this day, especially in New York at my Friday

night workshops where many of the participants are Jewish

people, they get horrified when I say that Hitler wasn't a

louse. He was a fallible, very disturbed individual who often

acted abominably

a person who did evil but not a totally evil man.

a person who did evil but not a totally evil man.

G: With my family's Holocaust background, I found your

comments yesterday about Hitler really confronting. I was

curious to understand how you reconciled not damning Hitler. You

explained that in fact you damned his actions, not him. That

distinction then made real sense. But hard to accept.

A: Yes, that's unconditional other-acceptance. People do do

bad things but they are never, never bad people.

Nor are they good people when they behave well.

G: Now my understanding of how definitive you are about

unconditional acceptance was clarified during our talk

yesterday. There is no qualification there.

A: Yes. You can always accept yourself and others, no matter

what you or what they do.

G: This unconditional acceptance has qualities almost akin

to divine acceptance.

A: Yes. But the divine is invented and probably doesn't

exist, while people are real and do exist. I'm not the only one

who advocates unconditional acceptance of people. And you can

accept people and yourself without hypothesizing a divine

acceptance. You can accept yourself because you think there is a

God who accepts you. But you can also do it, without inventing

any gods.

G: Perhaps we'll come back to that. I'd still like to

explore how, with your profound sensitivity, you coped during

the war years. The saying 'necessity is the mother of invention'

would suggest that the war years were triggers for your

response, through extreme creativity, to develop your new system

of thought, as a way to cope with the extreme confrontation the

war provoked in you, especially being a pacifist.

A: Well, not only the war but Hitler and Stalin after the

war.

G: Can you say more.

A: Hitler as you know killed 6 million people, mainly Jews,

Gypsies, communists and pacifists. Stalin killed about

50 million

he was worse in many respects, with famine and everything else.

Therefore, I gave up the idea of having a dictatorship of the

proletariat that supposedly would wither away as Lenin said it

would. So the war was bad enough, very stupid in most respects,

but Hitler and Stalin, you might say, were a little worse. They

devoutly believed in burning people.

he was worse in many respects, with famine and everything else.

Therefore, I gave up the idea of having a dictatorship of the

proletariat that supposedly would wither away as Lenin said it

would. So the war was bad enough, very stupid in most respects,

but Hitler and Stalin, you might say, were a little worse. They

devoutly believed in burning people.

G: Now, against this background, do you think there is a

link that prompted you to enter psychoanalysis in 1947?

A: That was after I got my PhD. My graduate programme was

mainly Freudian and Rogerian. I waited until I got it out of the

way, I didn't want it to interfere and then I immediately went

for analysis. I was not disturbed, but I wanted to train and be

accepted as an analyst, so I had to be analysed.

G: So in 1947, your career decision is to be an analyst.

You have your personal analysis and training. Six years later,

you turn 180° against psychoanalysis. Why?

A: Well, the main thing is that I'm an empiricist. So I

practised analysis, but mine was a fairly liberal analysis. My

analyst was a psychiatrist, was a follower of and a friend of

Karen Horney, and also an existetialist. So I was never a

pronounced Freudian. But my technique was at first fairly

orthodox.

My analyst used free association and really listening to his

analysands. So I tried his method and ran up against all kinds

of problems. I decided to give homework because I saw that

people really didn't change unless they pushed their arse to do

things differently. So I thought I would sneak in homework. But

then I concluded in 1953 'this psychoanalysis is crap!' So I

gave it up almost completely and went back to active-directive

psychotherapy and started to develop REBT.

G: And so in your analytic practice you are increasingly

frustrated with your patient's lack of change. So you prescribe

some homework?

A: Yes, I started prescribing homework. I was analysing a shy

woman who understood all principles of analysis, but still

wouldn't go out and talk to a man. She was scared shitless, and

don't forget I used in vivo desensitization on myself

when I was 19.

G: Would you like to briefly describe that episode when

you desensitized yourself?

A: Well, I saw that I was scared shitless of talking to

women. I flirted with them, but never approached them. So I said

this is silly philosophically. What is there to lose or to be

ashamed of? If they're going to reject me, are they going to cut

my balls off? So I gave myself a homework assignment to go to

Bronx Botanical Gardens every day in August and whenever I saw a

woman sitting alone on a park bench, whatever shape or size she

was, I would talk to her. I would sit next to her, not on a

bench away from her, and I gave myself one lousy minute to talk

to her. If I die, I die!

So I found a hundred and thirty women sitting on a bench

alone and sat next to all of them. Thirty got up and

walked away immediately; but I spoke to a whole hundred of them

about the birds, the bees, the flowers, the season, any goddamn

thing, and if Fred Skinner, who at that time was teaching at the

Indiana University, had known about my exploits, he would have

thought I would get extinguished! Because, of the hundred women

I spoke to, I only made one date and she didn't show up! But I

went on to the second hundred and started making dates.

G: That proves you're an optimistic empiricist for sure.

You didn't follow the dogma of the day, Skinner's extinguishing

theory. Left with little option, you were bound to develop your

own theory?

A: Right, I kept developing my own theory, mainly for working

with clients.

G: I'd like to explore this relationship between your

theory derived from work with clients, and relating to your

personal anecdote, working on yourself. How do you find the

balance between using your new ideas on yourself and your

clients

which comes first?

which comes first?

A: Sometimes, I've done it for myself first, like this in

vivo desensitization. But at other times, I just figure,

well what I'm doing now is not working with my client. What will

work? Let's experiment. I'm an experimentalist, so I try

something

some things don't work, but other things do. So I keep

incorporating in my theory the things that sometimes work.

some things don't work, but other things do. So I keep

incorporating in my theory the things that sometimes work.

G: So your theory has been evolving from principles from

your childhood, side by side with the mature, fully flourished,

later validated life experiences.

A: Yes, I experimented even as a child on me and then later

on me and my friends.

G: Yet for all your troubles, when you present your work

to the psychological, analytic and wider mental health

community, they're hostile.

A: They were very hostile.

G: How did you relate to hostile critics at that stage

when you were inventing your ideas in the mid 1950s?

A: The same way as to the women who rejected me at the age of

19. Too damn bad! They're prejudiced against my view, I'm

prejudiced for mine. We'll never meet. Who gives a shit

what they think of me?

G: Well, that makes sense at one level. Yet, as a

scientist, needing to validate your clinical evidence to advance

your ideas, you need peer discussion, feedback, acceptance in

order for your ideas to be adopted and your ideas eventually

become one of the most influential psychological paradigms of

the 20th century. The father of REBT, you become one of the most

highly quoted psychologists. Clearly, you must have been in

dialogue with many colleagues. How did you overcome the intense

criticism?

A: Well, I first won over a few and then I started recording

my REBT sessions and sending them out to people, like friends

and then other psychotherapists. I also kept writing, writing,

writing and talking, talking, talking and soon convinced more

and more therapists. Ten years later, Aaron Beck, Donald

Meichenbaum and other cognitive behaviour therapists got into

the act. Beck was also an analyst at first, started doing

cognitive therapy 10 years after I had already published on

REBT.

G: Can we explore the differences between Beck's cognitive

therapy and your REBT

how do you distinguish between them?

how do you distinguish between them?

A: Well, I recently wrote a paper and he wrote one with

Christine Padesky, showing the similarities and differences.

Beck is largely informational processing and does what I

originally did, but I have become more philosophical. I teach

people the general philosophy of self-acceptance,

other-acceptance and world-acceptance and Beck really doesn't do

that.

Also, I added all kinds of behavioural and emotional

techniques that I took from others or made up to include in

REBT. Like my famous shame-attacking exercise, which I made up

because I said right at the beginning in 1956 in my first paper,

'Thinking goes with feelings and behaviours. Feeling goes with

thinking and behaviours. Behaviour goes with thinking and

feeling.' All three! That's the way humans are. So REBT includes

a great many thinking, feeling and behavioural methods.

G: Yes. You say that's your philosophical foundation

contrasted to Beck's more narrow informational. It could almost

be said that REBT verges on the philosophical spiritual.

Do you think that's a fair assessment? spiritual.

Do you think that's a fair assessment?

A: Some people think so because part of REBT promotes

unconditional other-acceptance, which some people call

spiritual. You don't just think of yourself, but you think of

the rest of humanity. I don't like the use of the word

'spiritual' because it has other meanings. But if you want to

call REBT spiritual, then many people think that it is. I met a

rabbi whom I taught some REBT, who said, 'You know you are the

most spiritual person I know. If you want to speak from my

pulpit, you can do so.'

G: Did you ask him why he thought that?

A: Yes, because he thought that REBT tries to help the

individual and all humanity to have a fully accepting philosophy

and not to damn anyone.

G: Your rational emotive behaviour therapy seems to me to

resonate with the Jewish mystical tradition, which includes

thought, speech and action as the garments of the soul. There's

a very powerful parallel with your 'rational' thinking,

'emotive' feeling and 'behaviour' action.

A: Yes. A psychiatrist in Upper New York wrote me a while ago

and sent me a paper on Maimonides, showing that Maimonides saw

some of the elements of REBT in the 12th century.

G: Maimonides' philosophy was to tread the middle path,

that balance is a better pathway to recovery from various mental

conditions. Did you study his writings?

A: No, I read them much later, after I had already created

REBT.

G: Let's turn to the development of the Albert Ellis

Institute, an impressive six-storey townhouse in New York. How

did you choose this site?

A: Well, I set up the Institute in 1959 from royalties on my

books. Initially, I ran everything from my private practice as a

psychologist. Then, in 1964, we wanted to get a larger place,

really expand it. We looked around and finally found this as a

very logical place, which we could buy for $200 000. We moved in

1965 and got it fixed up a bit. The Woodrow Wilson Institute had

been here for 10 years before us.

G: So next year will be the 40th anniversary of your move.

A: Well it's going to be the 50th of my founding of REBT, in

1955.

Debbie: There's going to be big celebrations in July 2005.

G: I presume the planning and the organization is well

under way. To return to the shame-attacking exercise you

mentioned earlier when you sing in public. Would you sing one of

your songs?

A: I usually tell people that my singing is a shame-attacking

exercise. I say I'm going to use my godawful baritone and you're

going to use your godawful baritones, tenors, sopranos, altos.

Let us all shamelessly sing out. This is Love, Oh Love Me,

Only Me! (The tune of Yankee Doodle.)

Love, oh love me, only me Or I will die without you!

Oh, make your love a guarantee

So I can never doubt you!

Love me, love me totally

Really, really try dear!

But if you demand love, too

I'll hate you till I die dear!

Love me, oh love me all the time

Quite thoroughly and wholly

My total life is slush and slime

Unless you love me only solely!

Love me with great tenderness

With no ifs or buts dear,

If you love me somewhat less

I'll hate your goddamn guts, dear! G: I'm sure it's not just the voice or lyrics, but also

your unique rendition which gives it that special quality.

What's another favourite song of yours?

A: Glory, Glory Hallelujah!

Glory, Glory Hallelujah Mine eyes have seen the glory of

relationships that glow

And then falter by the wayside as love and passions come

and go

Oh, I've heard of great romances where there is no

slightest lull

But I am getting skeptical!

Glory, Glory Hallelujah! People love you till they screw

ya

If you'd lessen how they do ya

Then don't expect they won't!

Glory, Glory Hallelujah!

People cheer ya then pooh-pooh ya,

If you'd lessen how they screw ya,

Then don't expect they won't! G: Clearly, someone might say that this is enough to turn

any lover cynical! Yet, you retain an honesty and vitality and a

passion. So knowing what can happen to love, how do you manage

to take that fact?

A: Well, you take a risk. If your love lasts for ever, that

would be most unusual. So you assume that it may not last, but

you enjoy it while you may.

G: How do you cope with the pain of losing love, when it

doesn't last, or when something that you invest yourself in goes

sour?

A: You feel healthily sorry, frustrated and annoyed but not

unhealthily depressed, anxious, and despairing. That is, if you

use REBT!

G: Debbie explained to me how to use the REBT Self Help

Form. I was a bit slow, but she persevered and eventually I

realized that, according to your REBT, there are unhealthy

negative emotions which you can transform into healthy

negative emotions.

A: Yes. REBT is almost the only therapy that says you'd

better feel healthy negative emotions, not destructive

ones.

G: Now why do you call grief a healthy negative feeling?

A: Well because it is. If somebody you love dies, you first

have positive feelings for him or her, and you want to have

healthy negative feelings of sorrow, regret, or sadness. You

certainly don't want to have no feelings. So we define

your grief as a healthy negative emotion.

G: So it's negative in the sense that it's on the

'downside' of human experience but necessary for growth.

A: You're losing by death something you really want, so you'd

better not be deliriously happy! But you also don't want to be

unhealthily depressed.

G: So what would you call a state when everyone else

around the person is quite down but the manic person goes on

shopping expeditions and does quite outrageous things? What

would you call that state?

A: Mania.

G: So there are both unhealthy positive and unhealthy

negative emotions?

A: Yes. Pollyannaism, for example, is an unhealthy positive

emotion.

G: You say quite rightly that most of the other cognitive

behaviour therapies do not attend to emotions. How could they

omit such an essential human experience?

A: Well, they're now dealing with emotions because they're

now copying my REBT. They have the cognitive and to some degree

they have behavioural, but they sort of neglected the emotional.

We never did. But, finally, Judy Beck in 1995 included several

emotional techniques in cognitive therapy. And some of the other

cognitive behaviourists have used emotional techniques for quite

a while.

G: I read in a recent review that you have moved from

Dr Freud to Dr Phil (the TV personality), meaning that you made

therapy accessible to ordinary people. You've transformed

culture by bringing therapy from the analyst's couch to the

wider culture. Do you think that's a fair summary of your life's

work?

A: Yes. I was one of the very first to show people how they

construct their own beliefs, feelings and behaviours badly and

how they can reconstruct them and could do it even without a

therapist if they read my books and followed them. I was the

first to have put real rational emotive behaviour therapy in

audio- and video-cassettes.

G: Your revolutionary spirit from your college days,

through your professional career, transforming the culture and

landscape of psychology seems to be your hallmark. Are you still

a revolutionary now?

A: Compared to many people, yes. But many psychologists were

against me, especially conservative academic psychologists,

because they were against popular books.

G: How do you classify your books?

A: Several of them are almost purely popular, but others are

for the profession and are both popular and, you might say,

academic.

G: You've never shied away from popularity, but it sounds

like you've certainly never compromised your standards in order

to be popular, either. Turning to your current work, I was

intrigued by the title, which is A History of the Dark Ages

the 21st Century. Could you briefly outline your views?

the 21st Century. Could you briefly outline your views?

A: I decided to write that when I was 19 and in college. I

was going to write it because the world was so rotten then and I

figured out that today we don't let blood because we know it's

wrong but we do do lots of other things that are stupid and

wrong, which we know are wrong. So this is the real Dark Ages,

because we have the knowledge and we don't use it.

I was going to write a book The History of the Dark Ages

the 20th Century, so I collected thousands of articles and I

never got around to writing them up, because I have too many

other things I am busy doing. But then I thought of doing it in

the 21st century. So I just used material from this century and

I've written this book that isn't published yet.

the 20th Century, so I collected thousands of articles and I

never got around to writing them up, because I have too many

other things I am busy doing. But then I thought of doing it in

the 21st century. So I just used material from this century and

I've written this book that isn't published yet.

G: What are your other current projects?

A: I have another book, called Is Self-Esteem a Sickness?

It shows how self-esteem, as against self-acceptance, is one of

the worst sicknesses ever invented. I expect a lot of opposition

because self-esteem has been pushed, pushed, pushed by most

therapists for many years.

G: It sounds to me like this is vintage Albert Ellis in

revolutionary form.

A: And I am revising another of my old books, Is

Objectivism a Religion? I said it was. So now I've revised

that. That isn't published yet. It's to knock down Ayn Rand's

fascist philosophy. Rand was ostensibly an objectivist but

actually she was highly emotional and she was fanatical in her

damnation of all non-capitalists. The book I'm now proofreading

is The Road to Tolerance, Rational Emotive Behaviour

Philosophy.[See

Postscript]

G: It sounds like you work a 25 hour day!

A: Oh, I've got along with Debbie's help.

G: I now appreciate your dedication to Debbie in your most

recent book.

You've been extremely generous with your time. I think its

time to wind down. To finish, a New York Times article on

you ends with the quote, "'While I'm alive', Albert Ellis said,

'I want to keep doing what I want to do, see people, give

workshops, write, and preach the gospel according to Saint

Albert' ".

A: That's just humorous.

G: I see the twinkle in your eye and your smile, broadly

grinning, would there ever be

A: I'm against all gospels.

G: Okay, so have you ever had a calling to become Rabbi

Albert?

A: Well, as I told you, several rabbis have wanted me to

speak in their temples.

G: Do you think their invitations convey a message?

Recruiting you to the pulpit?

A: Well, some of them are very rational.

G: If some are very rational, what about the others?

A: Well, not the orthodox. They're often dogmatists.

G: So how does dogmatism and mysticism relate in your

scheme of things?

A: Well, dogmatism means that you say something and it's

absolutely true for all time because you believe it is and

mysticism says that we know the essence of it all, we can't tell

you what it is but we know it. There are some mystics who are

rational and some are irrational, so they all overlap to some

degree.

G: If you were to be invited by a rabbi, would you accept

the offer to speak from a pulpit?

A: Why not?

G: This is the revolutionary next phase perhaps?

A: Right.

G: Just briefly, before we finish, I'd like to recap from

our talk yesterday, as I was intrigued by your reflections on

the ADHD experience in America. You mentioned that you felt that

with the drugs that were introduced in the 50s to treat mental

problems, you had an elegant word to describe the drug's actions

'derigidicize'? 'derigidicize'?

A: Yes, derigidicize some of the mental symptoms.

G: Some people said that you felt that the advent of

psychotropic drugs adds more and more support to REBT. I am

curious about your thoughts on the decade the 90s, with the huge

increase in children with ADHD. You said, I think, that you

thought such children had two problems, one, the biological

problem that was the ADHD and then a secondary one, with how

they felt about their ADHD.

A: Putting themselves down for not being competent in our

culture.

G: Yes, you also emphasized the importance of competence

in all cultures, but not all cultures dole out as much

psychotropic medication.

A: Well, it's like psychosis. Psychosis involves a great deal

of incompetence. Psychotics are often able to do the things that

other people do, and in our culture and most cultures, even

children are supposed to be competent, get high marks and be

good at sports. So when children with ADHD see that they don't

understand things the same way as other kids do, they often put

themselves down, saying 'it's not good and I'm no good'. So that

adds enormously to the biological handicap of ADHD.

G: And this aspect would be accessible to treatment with

the REBT approach to alleviate their self attack in combination

with medication.

A: Yes. Even with schizophrenia we get them to accept

themselves as schizophrenics.

G: So that would be the model that you would use in ADHD?

A: Right.

G: Wonderful, I just wanted to clarify that. Thank you

very much for your time and for your unique rendition of your

songs and to Debbie for arranging this delightful meeting! |